The US needs more physicians

In the next decade, health care in the United State will be impacted by a dramatic shortage of physicians across both primary and specialty care. The Association of American Medical Collages (AAMC) estimates this shortage as up to 124,000 physicians by 2034. The aging of our nation’s population will contribute to this metric two ways, as more than two in five active physicians will retire in the next decade, while demand for specialties that care for older patients increases.

Physician burnout is also a factor, as the AAMC reports that 40 percent of practicing physicians felt burned out at least once per week — even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. With health professionals retiring sooner or reducing workloads to combat burnout, fewer professionals will see more patients, creating a cyclical problem. In a May 2022 advisory, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called health worker burnout “a growing threat to our individual and collective health.” When health care workers suffer, our communities also suffer.

And this shortage is likely underestimated. Health care use patterns by marginalized populations — such as those without health insurance or living in rural communities — don’t tell the full story. Without those barriers throttling access to care, an additional 180,400 physicians would be needed to meet even current needs. Addressing the current and growing physician shortage calls for integrated solutions, an important step toward which is medical school enrollment.

While racial and ethnic diversity in the US population has increased steadily for generations, this is not reflected in the medical student population. Students whose race or ethnicity is underrepresented in medicine are not increasing in significant numbers in medical schools. Of the 4,550 new seats in the 12 medical schools established in the past decade, only five percent have been filled by African Americans. Even Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have seen a decline in black applicants and matriculants.

These disparities extend to other underrepresented groups, too. American Indian and Alaska Native people account for less than one percent of medical students, and first-generation college students account for only 12 percent — both underrepresented compared with their US populations. From these statistical gaps come real-life consequences. Many people of color are missing out on rewarding careers in medicine, while the profession is missing out on the contributions of individuals who have unique perspectives, knowledge, and lived experiences to offer our field.

Perhaps most disconcerting is that many patients cannot see themselves reflected in their health care providers. Having a physician who might look like them, and who understands their culture and history, can help foster trust — which in turn can lead to better engagement, more adherence to health care recommendations, and better health outcomes.

If academic medicine is able to expand the pathway to becoming a physician to accommodate all demographic groups, we can help more people become the physicians this country so desperately needs in the next decade and beyond.

The overwhelming majority of effort to educate more students who are underrepresented in medicine has been made by Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HCBUs) and Minority Serving Institutions.

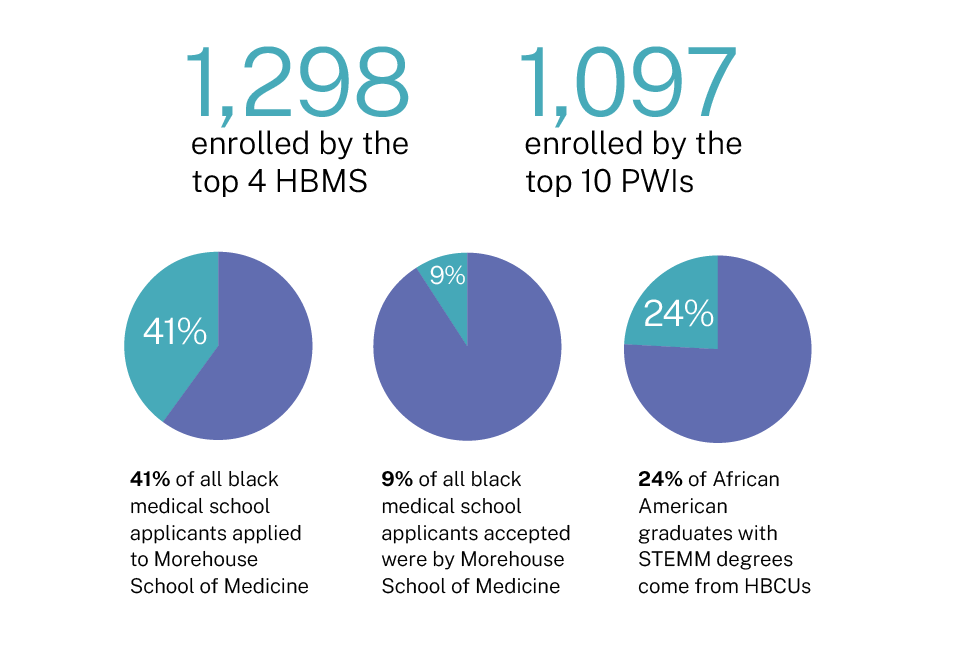

Since 2019, just four HBCUs have been producing half of the Black doctors in the country: Howard University in Washington, D.C.; Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles; Meharry Medical College in Nashville; and Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. And in 2021 – 22, these four schools enrolled more African Americans than the top ten predominantly white institutions combined.

If all 154 US medical schools had accepted an equal share of the black applicants, Morehouse School of Medicine acceptance percentage represents more than 90 times that of what would be expected for its medical school peers.

A partnership that aligns mission and leadership

As validated by the AAMC and other thought leaders involved in improving diversity through community collaborations, initiatives like the More in Common Alliance offer a solution to these representation issues.

An integrated approach

The More in Common Alliance strategy to increase diversity in undergraduate medical education has two distinct prongs, unified by community need.

Find out more about

- Residency expansion at CommonSpirit Health facilities

- Regional training sites at CommonSpirit Health facilities

- Community outreach to middle school, high school, and undergraduate learners

- Health equity and representation

- Staying informed about these issues

- Making a gift to support the More in Common Alliance